The social reality of free-lance musicians in Germany: should music colleges address this, and if so, how?

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the debate surrounding the potential future closure of music colleges in Baden-Württemberg in Germany in 2013. The minister who suggested reducing the number of places offered on undergraduate and postgraduate music courses from 2500 to 2000 based this on reports that there was an over-supply of music graduates relative to employment possibilities. I argued that music colleges in their capacity to educate creators of cultural value potentially have an important part to play regarding social cohesion at a societal level, and therefore shouldn’t be shut down.

This is all well and good, but how does it sort out a potential issue with over-supply of music graduates on the market, if there is one at all?

Esther Bishop’s MA thesis examines the status quo of employment possibilities for performance graduates and questions whether the structure of music colleges in Germany is appropriate in the context of today’s employment opportunities.

Of the situation in 2014 compared to the past she writes: “Significantly more musicians work as free-lancers and there are more free-lancers than salaried musicians … most music performance graduates will work in other professions than that which they intended.” (2014:9).

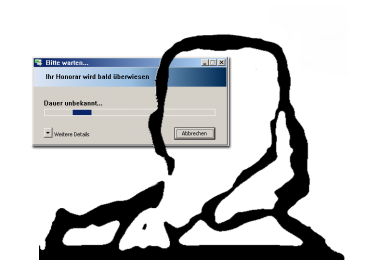

Statistics on the Musikinformationszentrum website suggest that in 2014, free-lance orchestral musicians’ average earnings were below the poverty line.

A few months ago, I discussed this issue with a group of performance undergraduates I was working with. Placing themselves in the position of a government with the responsibility of solving a very real issue they argued back and forth about the impact closing a music college or reducing the student intake would have for the staff, the other students, the prestige of the college and of the town or city in which it was based, and also the issue of raising students’ expectations that they would find work on graduating whilst knowing how unlikely this would be. The students at first agreed that they could see no other way to solve the problem than to reduce the number of music graduates by reducing undergraduate intake (with the concomitant loss of teaching jobs and prestige) just as Ministerin Bauer had done in Baden-Württemberg.

I argued as above, that music colleges should stay open because of what they are worth to society in terms of cultural value. I suggested that there may be other ways to address this issue and asked them how much they were learning about entrepreneurship during their course of study – that is, the kind of entrepreneurship knowledge that they would need if they did not win an audition for a salaried position in a state-run orchestra after graduation, in Bishop’s words: “Other difficulties faced by performance graduates include the differences in skills necessary to be free-lance rather than in a salaried position. Self-organisation, communicative skills and creativity are competencies described as being far more important in a free-lance context than they are required by salaried orchestral musicians.” (2014:10).

The college they attended either doesn’t offer such a course, or they didn’t know about it, certainly their current studies didn’t address acquisition of the particular skill-set required by free-lancers.

My research project with HIP orchestral musicians – all of them free-lance because that is the only option in HIP in Germany – gave me insight into the day-to-day working of the skill-set required by a cultural entrepreneur as defined by Swedberg “the carrying out of a novel combination that results in something new and appreciated in the cultural sphere.” (2006:260). HIP musicians seem to be particularly good at being cultural entrepreneurs, perhaps because the mind-set that informs HIP requires a calling-into-question of received performance parameters.

Based on my insights I proposed to my student interlocutors a study module intending to simulate a free-lance context within the safe space of the music college in which teaching consists of a hands-on approach to solving free-lance issues such as fund-raising, project management, and concert dramaturgy. I argued that introducing such courses would open up new employment options for students on graduation, also in other areas than music, since they would have gained transferrable skills that could be implemented in other contexts.

In the best of all worlds this might mean that music colleges, by rethinking how they can address the issue of over-supply and appropriate qualification, by nurturing students’ entrepreneurial potential and engagement with cultural value through their instrumental studies, might educate citizens who can navigate both the world of economic value as well as that of cultural value.

I will be presenting this module in April at the “First international conference on entrepreneurship in music” in Oslo, Norway.